A context for praying about Suicide

If you have Domestic Violence, Abuse or Suicide issues, please seek professional advice

on how to protect yourself, as well as seeking prayer support.

“Prayer with a person experiencing loss from suicide is a time to listen, to sit still, and to be present. It is a time to make space for expressions of rage, of agony, of astonishment, and of rejection of faith. It is a time to make it possible for stories to be told about loved ones now gone. “Tell me what your mother is like.” “What is one of your favorite memories?” You might ask someone how he or she imagines the moments after the loved one’s death. You do not have to find those ideas compatible with your own or give a lecture about Christian doctrine—your call is to offer the survivor the gift of attentive listening. It can be difficult to remember that companionship and prayer in silence can be much more effective than words, no matter how eloquent, when the unthinkable has happened. A willingness to stay with someone through the wilderness is of far more significance than the most profound speech made in an attempt to lead someone prematurely into a space of healing.”

Rev. Mary Robin Craig in ‘Praying with People Grieving Loss from Suicide’ @ Pittsburgh Theological Seminary

An Extract from “The History of Suicide”,

created by the Baton Rouge Crisis Intervention Center

Early Jewish/Christian Struggles

During the early years of Christianity, many believers chose suicide over the difficult life of religious persecution. In fact, some early Christian writers maintained that a self-chosen death was a goal for the genuinely pious to aspire. The number of Christian martyrs and mass suicides rose so quickly that the ruling Jewish faction decided to forbid eulogies and public mourning for those who died by their own hand. This action began the stigmatization of suicide in Judeo-Christian culture. The first church-led condemnation of suicide occurred when Jewish leaders refused to allow the bodies of Christian suicide victims to be buried in hallowed ground. The few Christian condemnations of suicide came from the notion that suicide was to be despised because it was the action of the betrayer of Jesus. Thus, suicide developed a “guilt by association” because of Judas’ death by hanging.

Christian Condemnation

The first Christian to publicly denounce suicide as a sin was St. Augustine in the 4th Century. The basis of Augustine’s condemnation was the ubiquitous acts of suicide among Christians. Augustine’s influence on church doctrine resulted in a series of conciliar developments. In 305AD, the Council of Guadix purged from the list of martyrs all who had died by their own hand. Using the pretext of piety, the 348AD Council of Carthage condemned those who had chosen self death for personal reasons and the 363AD Council of Braga condemned and denied proper burial rites for all known suicides. Although meant as a preventative measure, Church condemnation festered the stigma introduced by Jewish authority years earlier. The act of suicide became immersed in shame and fear, remaining so for the next nine decades. In the 13th century Thomas Aquinas fortified the Church’s official position against suicide. Unlike Augustine, who acted to quell the surge of suicide among Christians, Aquinas was motivated by a need for intellectual understanding. Aquinas completed a comprehensive and systematic review of Christian theology, entitled Summa Theologiae. In this work, Aquinas vilified suicide as an act against God (much like Socrates) and denounced suicide as a sin for which one could not repent. Aquinas’ admonition resulted in civil and criminal laws to discourage suicide.

The Middle Ages

As a result of religious, civil, and criminal sanctions against suicide, the social stigma of suicide reached menacing heights during the Middle Ages. Not only was a person who died by his own hand not allowed a proper burial, the custom of disgracing the body of a suicide victim became common. ...The property and possessions of the deceased, as well as that of the family, would be confiscated. Anyone who attempted suicide would be arrested, publicly shamed and sentenced to death. The seeds of social stigma against attempters, completers and survivors of suicide truly took root during the Middle Ages.

19th - 20th Centuries

The notion that mental or emotional distress could be caused by natural, physical factors helped pave the way for changes in civil, criminal and religious laws concerning suicide. Many countries began to abolish laws that made suicide a crime. In 1983, the Roman Catholic Church reversed the canon law that prohibited proper funeral rites and burial in church cemeteries for those who had died by their own hand. All of these developments have been instrumental in shifting attitudes about suicide in modern society.

Baton Rouge Crisis Intervention Center, ‘The History of Suicide’.

via the website of the Jacob Crouch Foundation.

<http://crouchfoundation.org/history-of-suicide.html>.

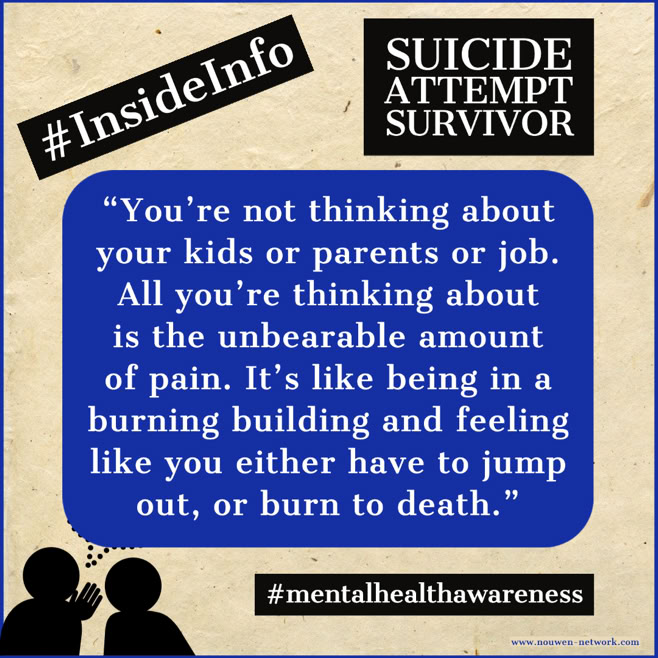

“The stigma surrounding suicide remains just high enough to discourage people - especially the elderly - from talking about their suicidal thoughts. Some people feel that they might be labelled as weak, lacking faith, coming from bad families or indeed ‘mad’ if they were to declare their suicidal thoughts. This does not help when we are trying to detect early signs of suicide or reaching out to help victims of despair.

Any approach to prevent suicide should include the removal of blame and stigmatisation of that individual and his or her family. One would hope that all teachers and professionals from the different faiths will take into account this insight into the condition. Scientific approaches and spiritual approaches can work together in order to eliminate this kind of stigma and to make people more comfortable in trying to seek help in their moments of despair.”

‘The stigma of suicide’ in British Journal of Psychiatry, Volume 179, Issue 2

https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/the-british-journal-of-psychiatry/article/stigma-of-suicide/8007A29C23705DC3A4F0CEF218A62380/core-reader

“Our ability for compassion and empathy and unconditional love is limited. When we meet certain barriers, we are helpless and can go no further. But God’s compassion can go through closed doors and closed hearts. It descends into hell. Most suicide victims are trapped persons, caught up in a private emotional hell which is an illness and not a sin. Their suicide is a desperate attempt to end unendurable pain, much like a man whose clothing has caught fire might throw himself through a window. They are not, on the other side, met by our human judgements, but by a heart, a companion, a love and a Mother whose understanding and tenderness is beyond our present imagination. She descends into their hell, holds them to her breast and breathes the spirit of peace and love over their fear and hurt. Then finally they experience that unconditional love and tensionless peace which eluded them during their lives on earth.”

- Father Ronald Rolheiser. (Oblate priest, theologian and popular spirituality writer) in Suicide, Despair and Compassion 1985

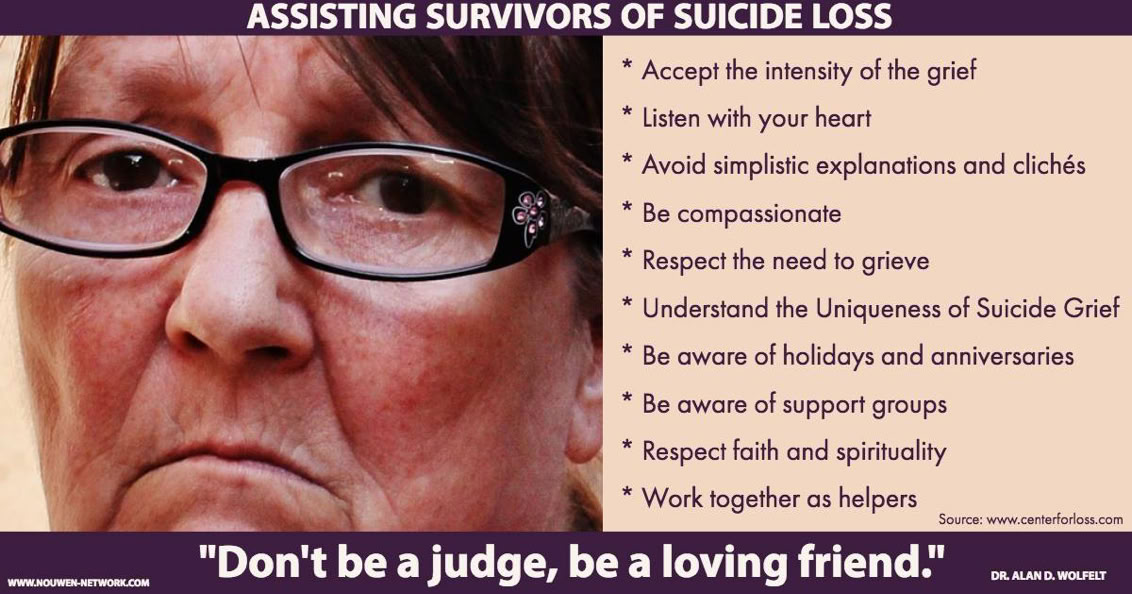

Respect Faith And Spirituality.

"If you allow them, a survivor will "teach you" about their feelings regarding faith and spirituality. If faith is part of their lives, let them express it in ways that seem appropriate. If they are mad at God, encourage them to talk about it. Remember, having anger at God speaks of having a relationship with God. Don't be a judge, be a loving friend.

Survivors may also need to explore how religion may have complicated their grief. They may have been taught that persons who take their own lives are doomed to hell. Your task is not to explain theology, but to listen and learn. Whatever the situation, your presence and desire to listen without judging are critical helping tools."

~ Dr. Alan D. Wolfelt, in ‘Helping A Survivor Heal’

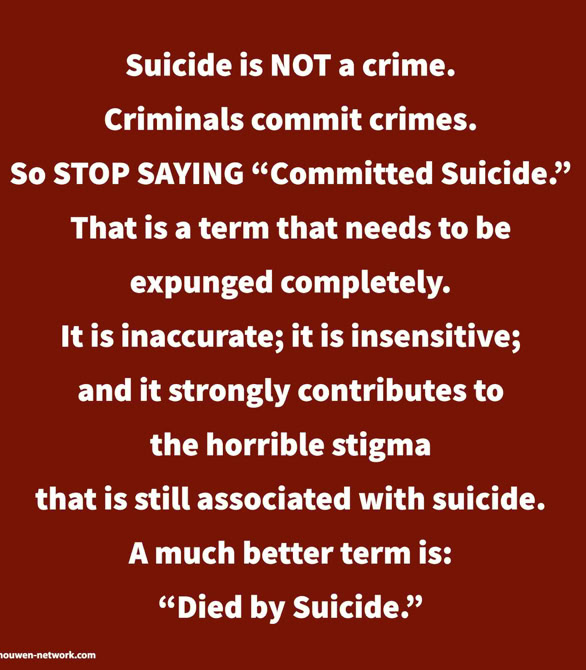

Non-Stigmatizing Choices

“So what can you say to destigmatize suicide and create a climate of healing and support? Experts suggest the following:

- Use the phrase “died by suicide” instead of “committed” or “completed” suicide. Similar to how we would describe that someone “died of an infection” rather than having “committed an infection,” this phrase communicates how they died but without the judgement and negative connotations.

- Use “suicide attempt” instead of “failed” or “unsuccessful suicide.”

- Avoid describing suicidal behaviors and non-suicidal self-injury as “gestures.”

- Avoid use of the word “suicide” in all contexts other than when referring to a person who has died by taking their own life (e.g., “fashion suicide” or “political suicide”).

- Describe the loved ones of an individual who died by suicide as “suicide loss survivors” to avoid confusion. When “suicide survivor” is used instead, sometimes people do not know if you are referring to a loss survivor or to a person who themselves has survived an attempt.

While making such shifts in our language may be just the tip of the iceberg when it comes to suicide prevention, these are relatively simple changes that we can all make to reduce the shame and stigma attached to suicide.

By reducing the stigma conveyed through our language choices, we can all create a space of understanding and support, allowing suicidal individuals the opportunities to step out of the darkness and access the help they need and deserve.”

Monique Kahn, Psy.D in ‘The Power Of Words: A Primer On Non-Stigmatizing Suicide Terms’ 2017.

“Loving God, you have promised you will never leave us. Ever. Yet there are people sitting in worship today who are feeling the most alone they’ve ever felt. Lives seemingly in despair. Hopeless. Isolation. Perhaps contemplating suicide. Perhaps scared for a friend or family member contemplating suicide. Perhaps grieving beyond belief for a loved one they’ve lost to suicide. Perhaps on the other side of darkness—a time when suicide seemed the only option, yet they are now filled with hope—yet still struggling with the memory of such darkness.

I pray, O God, that you will fill each person here with a sense of your love, your unconditional compassion—no matter what has happened, what they’ve done or not done—help us to feel a sense of belonging—to you, to each other. Help us to feel hope—maybe a small ray of light for the first time in a long time. You said you’d never leave us—ever. Help us to believe your promise. In your name—amen.”

Written by people who attended Soul Shop For Faith Leaders

Learn more about Soul Shop